Sails

From CruisersWiki

Cruising Yachts

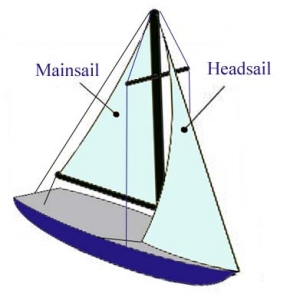

The most common sail plan for cruising yachts is the Sloop. This has two sails in a fore-and-aft arrangement: the mainsail and the jib.

The mainsail extends aftward and is secured the whole length of its edges to the mast and to a boom also hung from the mast.

The jib is secured along its leading edge to a forestay strung from the top of the mast to the bowsprit on the bow of the boat. A genoa is also used on many cruising yachts - it is a type of jib that is large enough to overlap the mainsail, and cut so that it is fuller than an ordinary jib.

Types of Yacht

Other yacht types that are seen on cruising yachts today include:

- Cutter -- this is the same as a sloop, but has more than one headsail (usually 2, although sometimes 3 or more).

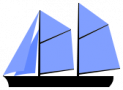

- Ketch -- this has two masts, where the foremost mast is the largest one (known as the main mast), and the aftermost mast (known as the mizzen mast) is smaller but forward of the rudder. Occasionally a cutter rigged ketch is seen, which has a main mast and a mizzen mast, and two or more headsails. This provides some of the advantages of the cutter rig but also the easier sail handling of the ketch rig.

- Yawl -- similar to a ketch in that it has two masts with the foremost mast being the larger of the two, but the mizzen mast is aft of the rudder. This design can often be seen as something that is converted from a sloop, as the mizzen mast is usually much smaller than the main mast and is situated well back on the boat (usually set with the boom overhanging the stern).

- Schooner -- this has two or more masts, where the foremost mast is not larger than the aftermost mast. The foremost mast is known as the foremast, and the main mast is at the stern.

The main advantages and disadvantages of each type are:

- Cutters often have more than one whisker pole, which is a pole that allows the headsail to be poled out beamwards of the boat. If there are two headsails and two poles then one sail can be poled out to port and the other poled out to starboard, which is an excellent rig for running dead down wind. In addition, a cutter rig can be made to point (sail upwind on a closer angle) in light to moderate winds better than a sloop by bending on both headsails. The main disadvantage would be that a cutter is harder to tack than a sloop because of the additional sail and stay that the main foresail (genoa) needs to be brought around. Also most cutters are made with the mast somewhat further back than that on a sloop, which impedes upwind performance.

- Ketches boast easier sail handling than sloops, because each of the sails individually is smaller than the mainsail of a sloop. Where the sails are large and the crew numbers are short, sail handling can become a difficult issue on a sloop -- this is made easier on a ketch. The downside is that a ketch does not point as well as a sloop or a cutter.

- Schooners have a unique advantage -- the ability to fly a gollywobbler, which is a large quadrilateral asymmetric spinnaker run between the two masts. This gives some advantage in light winds that are on or near the beam. The main disadvantage of the schooner is that it does not point as well as any of the other rigs.

Sail Plans

Note that a sail plan for a yacht is not actually limited in its meaning to the type of ship that is sailing -- there can be different types of sail plan for a yacht depending on the wind speed and direction. For example a yacht might have a light air sail plan including a spinnaker, a working sail plan which may include just the genoa and mainsail, and a heavy weather sail plan which may include just a working jib or storm jib and a trysail.

See also sail plan and types of ship on wikipedia.

The image below is from a sail plan for a cutter rigged cruising yacht. The sails carried are: asymmetrical spinnaker, genoa, staysail (jib), and main sail, and there are two poles on the mast.

Types of Sail

There are two basic types of sail in use on sailing boats since people ever started to sail on the ocean:

- Fore-and-Aft Sails

- Square Sails

Fore-and-aft sails can be switched from one side of the boat to the other in order to provide propulsion as the sailboat changes direction relative to the wind. When the boat's stern crosses the wind it is called gybing and when the bow crosses the wind, it is called tacking. Tacking repeatedly from port to starboard and/or vice versa, called "beating", is done in order to allow the boat to follow a course into the the wind.

Square sails are rarely seen these days except on the largest of sailing vessels. These are sails that run across the width (beam) of the boat rather than along the fore-and-aft line. They are usually only set when running downwind, and even on a large traditionally rigged ship there are also fore-and-aft sails for upwind work. A symmetrical spinnaker can be thought of as a square sail of some kind.

Fore and Aft Sails

Modern sails can be classified into three main categories and "special-purpose" sails are often a variation of the three main categories.: Mainsail, Headsail, Spinnaker or downwind sail (also known as a Kite).

Most modern cruising yachts including bermuda rig, ketch and yawl boats have a sail "inventory" which usually includes more than one of these types of sails. Although the mainsail is “permanently” hoisted while sailing, headsails and spinnakers can be changed depending on the particular weather conditions to allow better handling and speed.

- Mainsails, as the name implies, are the main element of the sailplan. A "motor" as well as a "rudder" for the boat, mainsails can be as simple as a traditional triangle-shaped, cross-cut sail. In most cases, the mainsail isn’t changed while sailing although there are mechanisms to reduce its surface if the wind is very strong (reefing). In extreme weather, a mainsail can be folded and a trysail hoisted to allow steerage without endangering the boat.

- Headsails are the main driving sails when going upwind. There are many types of headsails with the Genoa and Jib being the most commonly used. Both these types have different subtypes depending on their intended use. Headsails are usually classified according to their weight (the relative weight of the sailcloth used) and size or total area of the sail. A common classification is numbering from 1 to 3 (larger to smaller) with a description of the use for example: #1 Heavy or #1 Medium/Light. Special types of headsails include the Gennaker (also named Code 0 by some sailmakers), the Drifter (a type of Genoa that is used like an asymmetrical spinnaker), the Screecher (essentially a large Genoa), the Windseeker and the Storm jib. Certain Genoas and Jibs also have battens which assist in maintaining an optimal shape for the sail.

- Spinnakers are used for reaching and running (downwind sailing). They are very light and have a balloon-like shape. As with headsails there are many types of spinnakers depending on the shape, area and cloth weight. Symmetrical spinnakers are most efficient on runs and dead runs (sailing with wind coming directly from behind) while asymmetric spinnakers are very efficient in reaching (the wind coming from the rear but at an angle to the boat or from the side).

- A gollywobbler as mentioned earlier is a 4 sided spinnaker that is usually only carried on a schooner. It has a similar effect as a spinnaker but is flown when the wind is much closer to the beam than would be useful for even an asymmetrical spinnaker.

Sail Design

A primary feature of a properly designed sail is an amount of draft, caused by the curvature of the surface of the sail. When the leading edge of a sail is oriented into the wind, the correct curvature helps maximise lift while minimising turbulence and drag, much like the carefully designed curves of aircraft wings. Modern sails are manufactured with a combination of broadseaming and non-stretch fabric. The former adds draft, while the latter allows the sail to keep a constant shape as the wind pressure increases. The draft of the sail can be reduced in stronger winds by use of a cunningham and outhaul, and also by bending the mast and increasing the downward pressure of the boom by use of a boom vang.

Aerodynamics of Sails

Sails propel the boat in one of two ways:

- When the boat is going in the direction of the wind (i.e. downwind), the sails may be set merely to trap the air as it flows by. Sails acting in this way are aerodynamically stalled. In stronger winds, turbulence created behind stalled sails can lead to aerodynamic instability, which in turn can manifest as increased downwind rolling of the boat. Spinnakers and square-rigged sails are often trimmed so that their upper edges become leading edges and they operate as airfoils again, but with airflow directed more or less vertically downwards. This mode of trim also provides the boat with some actual lift and may reduce both wetted area and the risk of "digging in" to waves.

- The other way sails propel the boat occurs when the boat is travelling across or into the wind. In these situations, the sails propel the boat by redirecting the wind coming in from the side towards the rear. In accordance with the law of conservation of momentum, air is redirected backwards, making the boat go forward. This driving force is called lift although it acts largely horizontally.

On a sailing boat, a keel or centreboard helps to prevent the boat from moving sideways. The shape of the keel has a much smaller cross section in the fore and aft axis and a much larger cross section on the athwart axis (across the beam of the boat). The resistance to motion along the smallest cross section is low while resistance to motion across the large cross section is high, so the boat moves forward rather than sideways. In other words it is easier for the sail to push the boat forward rather than sideways. However, there is always a small amount of sideways motion, or "leeway".

Forces across the boat are resolved by balancing the sideways force from the sail with the sideways resistance of the keel or centerboard. Also, if the boat heels, there are restoring forces due to the shape of the hull and the mass of the ballast in the keel being raised against gravity. Forward forces are balanced by velocity through the water and friction between the hull, keel and the water.

Sail Parts

The lower edge of a triangular sail is called the foot of the sail, while the upper point is known as the head. The lower two points of the sail, on either end of the foot, are called the tack (forward) and clew (aft). The forward edge of the sail is called the luff (from which derives the term luffing, a rippling of the sail when the angle of the wind fails to maintain a good aerodynamic shape near the luff). The aft edge of a sail is called the leech.

Modern sails are designed such that the warp and the weft of the sailcloth are oriented parallel to the luff and foot of the sail. This places the most stretchable axis of the cloth along the diagonal axis (parallel to the leech), and makes it possible for sailors to reduce the draft of the sail by tensioning the sail, mast and boom in various ways.

Often tell-tales (small pieces of yarn), are attached to the sail that are used as a guide when trimming the sail.

Measurement

Every sail-plan has maximum dimensions. These maxima are for the largest sail possible and they are defined by the image's (right) letter abbreviation.

- J The base of the foretriangle measured along the deck from the forestay pin to the front of the Mast.

- I The height measured along the front of mast from the jib halyard to the deck.

- E The foot length of the mainsail along the boom.

- P The luff length of the mainsail measured along the aft of the mast from the top of the boom to the highest point that the mainsail can be hoisted at the top of the mast.

- Ey The length of a second boom (For a Ketch or Yawl).

- Py The height of the second mast from the boom to the top of the mast.

Fitting

Details?

Maintenance

Cleaning Sails

We clean our sails at least once a year, bringing them ashore where they can be laid out. We do it early in the morning on a sunny day. Using a relatively soft brush (so we don't damage the sail cloth or the stitching) we use regular liquid laundry detergent, then hose off. We check over the sail first, to determine if there are any bad stains. Rust stains (which will destroy your sail really quickly) we remove by putting either oxalic acid or hydrofluoric acid (the latter is found in commercial rust removers) onto the stain, watching it work and rinsing it off thoroughly with the hose immediately. CAUTION: both the above acids do more damage to the tissues and nerves than to the skin, so it's a silent and nasty poison that does its damage before you realize there's anything wrong. Do wear rubber gloves and be careful. That said, I think that both acids are extremely useful on a boat, so we always have a supply. We just are careful using them.

DuPont recommends a mild solution of chlorine bleach to remove mildew stains from dacron sails (but never, never use chlorine bleach on nylon). We usually use liquid non-chlorine bleach (such as Clorox 2(tm)), full strength on the stain before washing the entire sail.

We then haul the sail up, on whatever line we can rig, for it to dry completely before we put it back on the boat. If you fold your sail up before it's completely dry, you run the risk of mildew forming, particularly if you then stow them in a locker.

Cleaning the sails this way gets us up close and personal with the sails, so we check over all the stitching while we're working. Broken stitches means we take it to be repaired right away before things go wrong.

Also see: Sail Care

Publications

Forums

- Rigging & Sails forum on Cruiser Log

Links

- Sail Plan on wikipedia

Also See

| This page has an outline in place but needs completing. Please contribute if you can to help it grow further. Click on Comments to suggest further content or alternatively, if you feel confident to edit this page, click on the edit tab at the top and enter your changes directly. |

| |

|---|

|

Names: Delatbabel |